In 2004, more than 62 million Americans voted to bring George W. Bush and Dick Cheney back for a second term. I'm sure that some of those millions did so to register explicit support for the Iraq war and everything that went along with it, from Guantanamo to Abu Ghraib. But for a lot of them the reasons were messier. They didn't like John Kerry, or his windsurfing. They objected to the Democrats' position on taxes or gun control. They were worried about this or that aspect of the economy. In the decisive state of Ohio, the 100,000+ vote margin for the Republicans may have depended on opposition to the state's gay marriage initiative. Democracy is messy, like life.

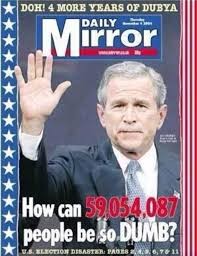

From outside the country, that messiness didn't matter. People read the results as an up or down verdict on the first four Bush years. And since from outside the country those years mainly amounted to the invasion of Iraq, America was seen as having voted thumbs-up on that decision. Thus front pages like the one at the right, from the Daily Mirror in England. (At the time of the headline, Bush's vote total was a few million short of its ultimate level.) It was too simple a reading, but inevitably it is how the world interpreted the results.

In 2015, millions of Israeli voters decided on a result that will bring Benjamin Netanyahu back for another term. I am sure that some fraction of them did so to register explicit support for Likud policy and all that it has meant. But even without being an expert on Israeli politics I am sure that for a lot of them the reasons were messier. They felt this way about the economy, they felt that way about possible opposition leaders, they voted for Likud as an alternative not to a party further left but one further right. Democracy is especially messy and unpredictable when mediated through a fluid multi-party coalition system.

From outside the country, that messiness doesn't quite register. People naturally read the results as a referendum on Netanyahu's very tough line on Iran negotiations and his recent, revised promise never to allow a Palestinian state. Thus they view the election as they did the U.S. results 11 years ago, as an explicit endorsement of a bellicose foreign policy. Including, in Israel's case, endorsement of stands (on Iran and the two-state prospect) at clear odds with U.S. policy and interests.

In his second term, the re-elected President Bush actually pursued a different policy than he had in his first term. Dick Cheney was corralled; the U.S. undertook no new wars and began repairing some of the relations it had frayed or broken. Four years later, the same U.S. electorate made an entirely different choice.

In Israel, this next stage of forming coalitions and setting policies will help the outside world understand what the latest election "means." If Netanyahu ends up forming a bloc that allows him to say: I ran tough, and I'll govern tougher, so shut up and get used to it, the rest of the world (including the U.S.) can react accordingly. But if he works out an arrangement that allows him to say: That was then, this is now, I recognize that for the good of the nation I need to choose another course, the world can react to that. I'm not expecting the latter, but there's no payoff in giving up hope.

This article was originally published at http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2015/03/elections-have-unintended-consequences/388195/