Back in 1982, The Atlantic published what I believe was the first article in a non-tech magazine about the implications of the then-dawning personal computer age.

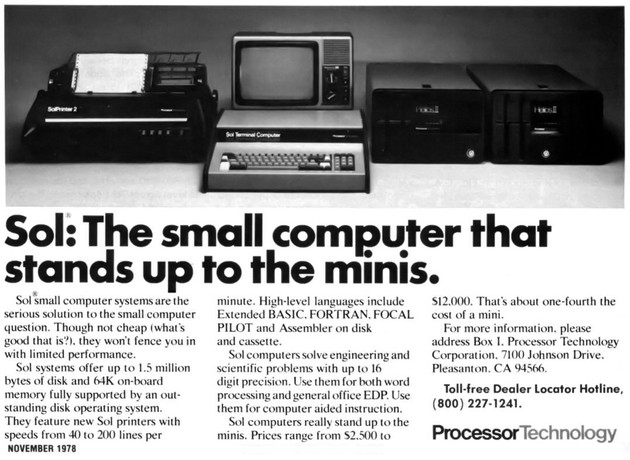

As it happened, the article was by me, and it concerned the way a single machine was changing my life. The machine in question was the one you see above: the Processor Technology SOL-20, by most reckoning the very first personal computer. The walnut siding on my model is still fairly lustrous, thanks to my taking it out of the basement for polishing every few years. If I could find a monitor to connect it to, and 5 1/4" disk-drives (or even Radio Shack tape recorders) to load a program, I believe it would still work. Many articles and my book National Defense came out of this machine.

The article I wrote in 1982, "Living With a Computer," has been online but in a poorly formatted version. My colleagues at the Atlantic, including those not yet born when I bought the machine, have now graciously put the story into better-looking typography. You can read it here.

Considering that we've been through 20+ cycles of Moore's Law since this came out, I think it stands up OK. It contains many howler anachronisms but also some reminders that as technology changes the human interaction with technology has surprising constants.

The story begins this way:

I'd sell my computer before I'd sell my children. But the kids better watch their step. When have the children helped me meet a deadline? When has the computer dragged in a dead cat it found in the back yard?

The Processor Technology SOL-20 came into my life when Darlene went out. It was a bleak, frigid day in January of 1979, and I was finishing a long article for this magazine. The final draft ran for 100 pages, double-spaced. Interminable as it may have seemed to those who read it, it seemed far longer to me, for through the various stages of composition I had typed the whole thing nine or ten times. My system of writing was to type my way through successive drafts until their ungainliness quotient declined. This consumed much paper and time. In the case of that article, it consumed so much time that, as the deadline day drew near, I knew I had no chance of retyping a legible copy to send to the home office.

I turned hopefully to the services sector of our economy. I picked a temporary-secretary agency out of the phone book and was greeted the next morning by a gum-chewing young woman named Darlene. I escorted her to my basement office and explained the challenge. The manuscript had to leave my house by 6:30 the following evening. No sweat, I thought, now that a professional is on hand.

But five hours after Darlene's arrival, I glanced at the product of her efforts. Stacked in a neat pile next to the typewriter were eight completed pages. This worked out to a typing rate of about six and a half words per minute. In fairness to Darlene, she had come to a near-total halt on first encountering the word "Brzezinski" and never fully regained her stride. Still, at this pace Darlene and I would both be dead—first I'd kill her, then I'd kill myself—before she came close to finishing the piece. Hustling her out the door at the end of the day, with $49 in wages in her pocket and eleven pages of finished manuscript left behind, I trudged downstairs to face the typewriter myself. Twenty-four hours later, I handed the bulky parcel to the Federal Express man and said, "Never again."

The rest is here. Thanks to my colleagues for digging this one out and refurbishing it.

This article was originally published at http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/04/what-was-it-like-before-electricity-daddy/389841/