Yesterday the ceilings were low and the weather was bad across the southeastern United States. In these circumstances, a Cirrus SR-22 aircraft that had started out in Canada, stopped to clear customs in Erie, Pennsylvania, and was ultimately headed to Florida apparently ran very low on fuel over North Carolina.

In the bad weather, the pilot was not able to land. With fuel diminishing, he pulled the parachute—as often discussed, these parachutes-for-the-whole-airplane are distinctive Cirrus features — and came down near a house in Kannapolis, North Carolina. Here is how the plane looked after it hit the ground (via screen grab from WBTV). The big orange-and-white thing is the parachute.

And another, via screenshot from Fox 46 in Charlotte, emphasizing the minimal damage to the airplane. More photos are at the aviation site Kathryn’s Report.

I’m being deliberately vague in discussing what might have happened and why. Mainly that’s because it takes a long time to know for sure. But also that’s because I want to emphasize this real-world specimen of how air-traffic controllers do their job.

If you listen to the clip below (via COPA, the Cirrus Owners and Pilots Association) you’ll find the action starting at time 13:15. First a pilot calls in from “Charlie Golf X-ray X-ray Juliet,” the phonetic pronunciation for a Canadian-registered plane C-GXXJ. (Canadian planes start with C, or Charlie; U.S. planes with N, or November.) He’s answered by a controller from Charlotte Approach, which handles traffic into and out of the very busy Charlotte airport. When neither is talking, you hear nothing at all.

At this stage, Canadian plane has just tried to land at the main Charlotte airport, was not able to (as will be explained), and is talking with the approach controller about what to do next. The controller says he understands that the plane is very low on gas, and offers to direct him “pretty much anything you want” (except Charlotte itself). The nearest feasible landing site appears to be Concord Regional airport, which has instrument approaches and a big, long runway.

The discussion proceeds from there, all the way until the end of this clip. More details after you’ve had a chance to listen.

***

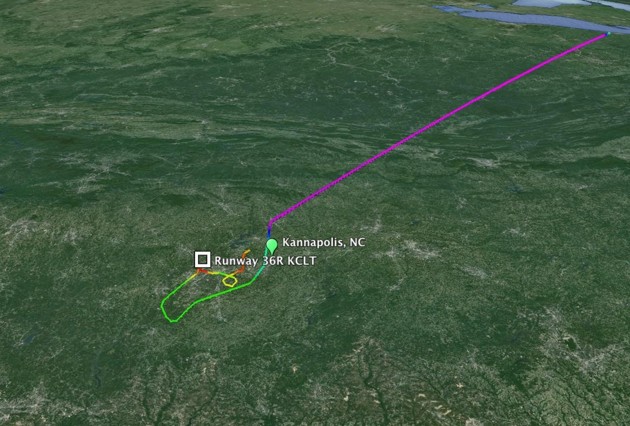

Rick Beach, who has directed safety efforts for the Cirrus pilots’ group COPA, has produced a sequence of three Google Earth overlays to show what is happening during the discussions captured in this clip. This is the big picture:

The airplane is headed south, from the upper right portion of this shot, and is headed for Charlotte, KCLT, in the lower left. At that time aircraft were “landing north” at Charlotte. So this plane goes south of Charlotte and does a U-turn, as shown in green, to line up for a northbound approach into the airport.

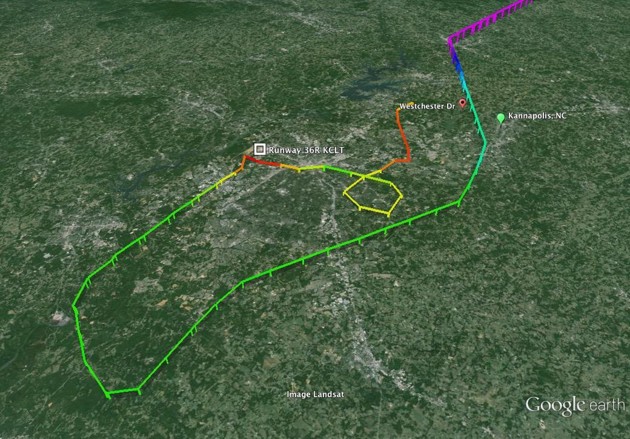

So far this is all perfectly normal. But after getting very close to the airport, the Cirrus doesn’t land there. Instead, following controllers’ instructions, it heads off toward the right (or east).

Here’s a closer view of what happened at Charlotte. The colors indicate altitude — the redder, the lower. This graphic shows that the plane descended as it neared Charlotte, then diverted to the right, circled, and climbed

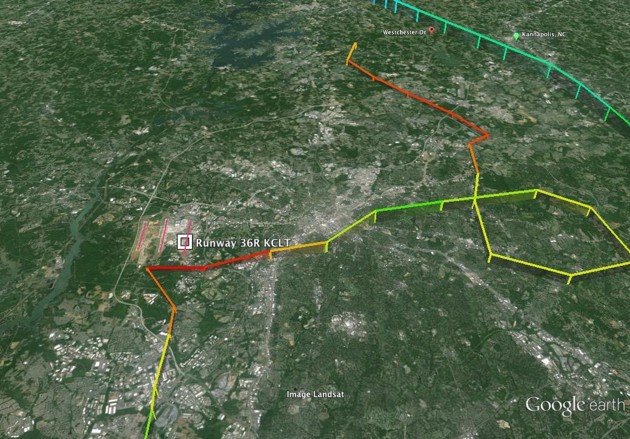

And an even closer view. Charlotte has three parallel north-south runways, which in this view are runways 36 Left, 36 Center, and 36 Right. I’ve highlighted them in magenta. The plane had been cleared to land on the rightmost, 36 Right. But it appeared to drift over toward 36 Center (where an airliner was waiting), and then apparently was told by controllers to break off from the approach and divert to the east. [See update below for more.]

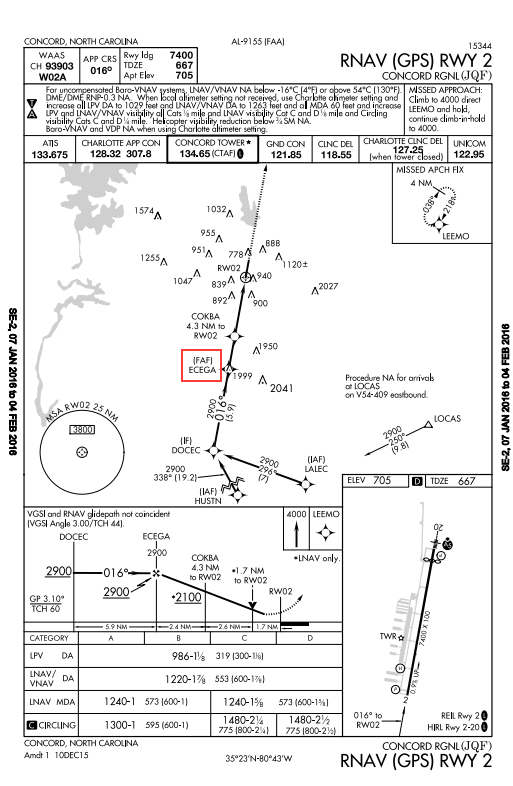

And since we’ve gone this far, here is the “approach plate” for the landing the controller initially recommends the plane try after Charlotte (RNAV GPS 02 at Concord). You’ll hear him directing the Cirrus to the waypoint I’ve marked in red, called ECEGA. For whatever reason that doesn’t work, and the controller switches him to a different approach (ILS 20). Some time after that the pilot pulls the parachute.

These details are for aviation buffs. I think the episode deserves notice from the broader public for two reasons.

***

The first is simply as a case study of the unflappable competence of the air traffic controllers, which is something I’ve mentioned before (eg last year) and that in my experience is the trained-for norm in their profession, rather than the individualized exception. Yes, controllers get mad; they get impatient; they make mistakes; sometimes those mistakes can cost pilots and passengers their lives. But most of the time I marvel at how smoothly and imperturbably they do their jobs. This clip gives an example.

The other reason is to emphasize the difference that the “ballistic parachute,” still unique to Cirrus among certified aircraft, has made. For the first few years after the system’s introduction in 2000, the fatal-accident rates in Cirruses was no better than in the rest of the general-aviation fleet, and in some years worse. One hypothesis was that pilots were reluctant or embarrassed to use the parachute, if they thought (often incorrectly) that they had any chance of getting the airplane down safely. Another was “risk compensation”: because people knew they had more safety equipment, they took more risks, and thus ended up no better off. (This is like the theory that you’ll drive faster on icy roads, if you know you have anti-lock brakes.)

Again, I’m deliberately stopping short of any “what this all means” point. I am offering this as a sample of how people do their work when the stakes really can be life or death. If the airplane had no parachute, or if sixteen other factors had gone a different way, the pilot you hear on this frequency might not have survived the day. The controllers had no idea how this would end, when they were speaking with him. That is why I find their self-possession notable.

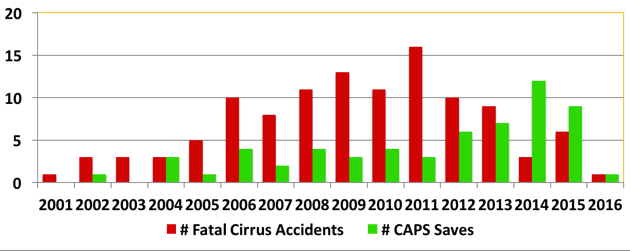

The trend has finally changed. This chart, prepared by Rick Beach of COPA, shows red, for fatal accidents in Cirruses, and green, for successful parachute pulls, in which those aboard escaped with no serious injury.

Due mainly to this change in behavior, the fatal accident rate for Cirrus aircraft is now much lower than for the fleet as a whole. (There are about 6,000 Cirrus aircraft in use around the world.)

***

Update: I have found the archive of transmissions from the Charlotte Tower, just before what we hear in the clip above. Around time 5:00 in this clip, the tower controller first talks with the Canadian Cirrus. At time 10:48, the tower controller clears the Cirrus to land on runway 36 right— but a few seconds later, he tells the Cirrus pilot that he is drifting too close to the center runway, where an airliner already is. He cancels the landing clearance and tells the Cirrus to turn right, and away from the airport.

At time 12:30, tower asks the pilot how much fuel he has left. The answer sounds like “17 minutes,” which is not very much. Just after time 13:00, tower tells the pilot to contact the approach controller — which is where we rejoin the other clip.