As part of the unfolding saga of start-up businesses as the crucial creators of new jobs, and of particular start-ups like craft breweries (along with tech incubators, arts companies, manufacturing “maker spaces,” and others) in bringing life to fringe areas of recovering cities, I talked about the civic and economic role of the Bent Paddle Brewery in Duluth, Minnesota.

Reader Peter Hatinen of Minneapolis says that Duluth is actually a test case of the Jane Jacobs-like process of distributed, organic revival that is happening a number of the cities we have visited and written about. The step-by-step evolution he’s describing is worth presenting in detail, because it has such resonance elsewhere.

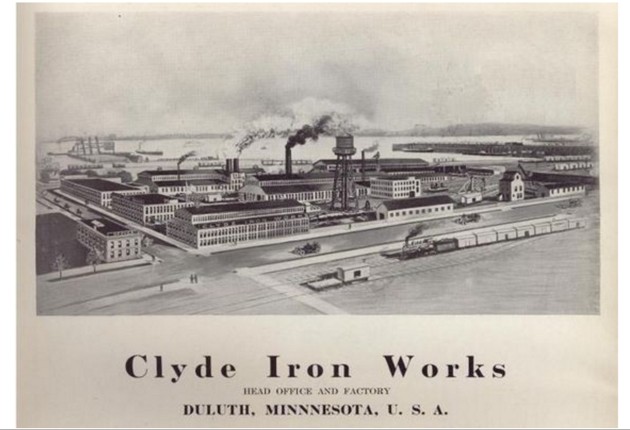

And for anyone who hasn’t (yet) spent time in Duluth, a city I love and have visited at least a dozen times since the late 1990s, it’s important to understand its economic background. Through the past generation Duluth has fit anyone’s definition of a struggling Rust Belt city. Its grand homes and faded-glory downtown buildings were from a lost era of wealth from timber, ore and grain shipments, and heavy manufacturing. Through much of the late-20th century Duluth’s factories closed, its downtown decayed, its population aged and shrank.

Recently a lot of has been changing, fast, as I sketched out in my recent story. Peter Hatinen describes more of what is going on:

After time in New York City and Boston, my wife and I settled in Minneapolis. Much of my family grew up and settled around Duluth. Since settling in Minneapolis ourselves, my wife and I have spent nearly every other weekend in Duluth during the summers, delighting in its restaurants, breweries, and distillery. We then pay penance for our indulgences by sailing, rowing, and running or biking the city's countless trails.

Duluth's renaissance has been remarkable. I suspect it started with the interstate tunnel project. Much like Boston's Big Dig, that project reunited the city with its gorgeous waterfront. That led to the burgeoning development in and around canal park which, in turn, spread eastward and up the hill toward the university.But, for a decade, or even two, it never spread west. That division of the city always saddened me. One thing I've loved about the city is the unique combination of industry and the stunning natural beauty of Lake Superior and the rock faces and bluffs that rise out of it. Why did the prosperity stop roughly at Mesaba Avenue?