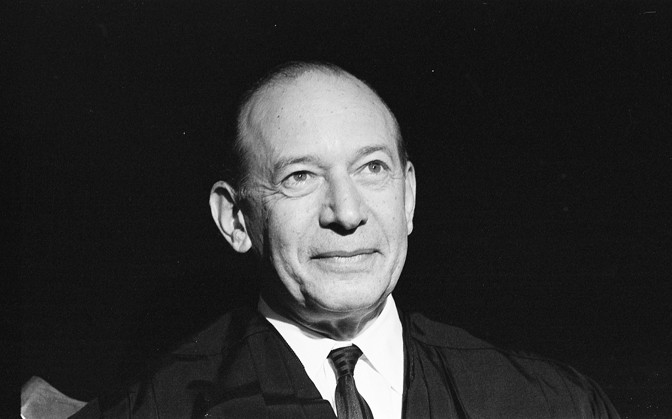

The most cynical decision George H. W. Bush made as president was to nominate Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court.

The choice was cynical because of Thomas’s race. In 1991 Bush had a vacancy to fill when Thurgood Marshall—the first African American ever to sit on the Court, the man who had successfully argued the historic Brown v. Board of Education case before the Court as a lawyer for the NAACP—decided to retire.

Clarence Thomas’s views were the opposite of Marshall’s on just about every front, as Juan Williams (then of the WashingtonPost, now best known from Fox News) explained in an Atlantic profile several years before Thomas’s nomination. But Bush knew that liberal critics of Thomas’s conservative views would be in a bind. If they opposed him—a graduate of Yale Law School, who had started out as a poor child in the segregated South—they would of course be blocking a black successor to America’s first-ever black justice.

Thomas himself left no doubt about this framing of events, saying in his opening statement to the Senate Judiciary Committee that criticism of him had amounted to a “high-tech lynching for uppity blacks who in any way deign to think for themselves.”

Bush’s cynicism came through in his announcement of the Thomas choice, implausibly claiming that “the fact that he is black and a minority has nothing to do” with the selection. The only reason for the choice, he said, was that Thomas was “the best qualified [candidate] at this time.”

The “best qualified” claim was risible. Thomas was 43 years old and had spent only a year-plus as a judge. In an editorial opposing his confirmation, TheNew York Timessaid:

If the Thomas nomination is to be judged on the merits, it fails.

The fault, in the end, is not that of the nominee but of the man who nominated him … By nominating this black conservative, President Bush serves a narrow partisan interest when the public has a right to expect him to nominate a lawyer or judge of proven distinction.”

But of course Thomas made it through a bitter confirmation process. He won approval from the Senate on a vote of 52-48 and took what had been Thurgood Marshall’s seat at age 43. He is only 70 years old now and conceivably could be on the Court through several more presidencies. Already he has been a fifth vote in such history-changing 5-4 decisions as Citizens United in 2010 (which ushered in nearly limitless money in politics); Heller in 2008 (which ushered in the novel concept that Second Amendment protection for a “well-regulated militia” extended to any individual who wanted to own firearms); and Bush v.Gore in 2000 (which ushered in … )

For more assessments of what Clarence Thomas has meant as a jurist, I refer you to my Atlantic colleague (and real-world law professor) Garrett Epps, here, here, and here, among other sources. Let’s focus for the moment on what his case means about the confirmation fight immediately in prospect, that of Brett Kavanaugh.

The Thomas and Kavanaugh cases differ in some obvious ways. Thomas was poor, black, and underprivileged by almost every measure. Kavanaugh, whose father was a long-time D.C. lobbyist who was paid $13 million in 2005, grew up on the opposite side of most calculations of racial and economic advantage. In terms of experience, Kavanaugh has been a federal judge for more than a dozen years, and has been rated “well qualified” for the Supreme Court by the American Bar Association, which the novice Thomas was not.

The similarity of the cases is the “now or never” nature of the criticisms of these candidates as people, and the consequent time pressure on their hearings. This is entirely apart from questions of substantive jurisprudence, for instance how Kavanaugh might rule in Roe v. Wade or on presidential powers. Instead these are questions of honesty, at several levels.

In Clarence Thomas’s case, the strongest argument against him as a person, and the one that provoked his angriest response, involved alleged sexual harassment—and whether he was being truthful in denying it. At his hearings, his former colleague Anita Hill was the only alleged victim of his behavior allowed to testify. The senator who then chaired the Judiciary Committee, Joe Biden (the Democrats held both the Senate and the House), notoriously prevented several other women from testifying, and treated Hill in a dismissive manner that many years later he apologized for.

In the decades since that hearing, accumulating evidence has piled up on Anita Hill’s side of this story (and the other women’s), and against Thomas’s. If you’d like to review the details, start with this recent piece by former New York Times editor Jill Abramson, who with Jane Mayer wrote a well-known book about the case; or a post by Jay Kaganoff, who has written for Commentary and National Review. In that article, called “Fellow Conservatives, It’s Time to Call on Clarence Thomas to Resign,” Kaganoff said that the mounting evidence had changed his mind. He concluded:

I believe Anita Hill. I believe that Clarence Thomas abused his authority to sexually harass a woman who worked for him. And lied about it. And smeared his accuser.

And got away with it.

“Got away with it” is the crucial point here. The “get away” / “don’t get away” decision point comes before a Senate vote, not ever afterward. Once a person is confirmed to the Supreme Court, he or she is, in practical terms, beyond all future accountability.

In principle, justices “should” recuse themselves from cases in which they have a potential conflict of interest. But no one can make them do so. Clarence Thomas’s wife, Ginni, is a long-time and highly paid lobbyist for right-wing political causes. To the best of my knowledge (I welcome new info), this has not ever led her husband to recuse himself from a case. As many news reports have noted, Brett Kavanaugh has been notably coy about whether he would recuse himself in cases involving the legally embattled president who is now appointing him. Obviously he “should” step aside in such instances—as Elena Kagan has recused herself in some cases involving the Obama administration, for which she was solicitor general. But absolutely no one could force him to do so, if he decided otherwise.

Also in principle, justices, like presidents, can be impeached. But this is even rarer for the Supreme Court than for the White House. It’s happened to only two presidents (Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton), and been threatened for a third (Nixon, just before he resigned). For the Supreme Court, it happened only once, in the early 1800s. Again, for practical purposes, whatever vote the Senate is about to hold on Brett Kavanaugh is the vote on whether he’ll be on hand through his 50s, 60s, 70s, 80s, or however long he is able to serve. And the 51 Republicans under Mitch McConnell’s guidance in the Senate are rushing to lock this in while they can. (These are mostly the same people who followed McConnell’s lead in denying a hearing to the Obama nominee Merrick Garland through nine full months.)

They want to get the vote done now—while they still have a 51-49 vote majority in the Senate, before the mid-term elections and whatever they might indicate about Donald Trump’s standing, before further legal ramifications from the Mueller probe. If they can get him in, he’s in.

***

How is this connected to Clarence Thomas? I explicitly do not imply a connection in the most obvious way: that the recent allegation about sexual misbehavior by Kavanaugh, back during his high school days at Georgetown Prep, is in any way comparable to the squelched multi-witness case against Clarence Thomas. I have no idea what to make of this claim about Kavanaugh—except that it seems worth listening to Anita Hill, who has just said that the charge should be considered in “fair and neutral” conditions, rather than in a partisan-driven rush.

The circumstances that to me resemble Clarence Thomas’s involve two other aspects of Kavanaugh the person, which the Senate can consider during a confirmation vote—but never again.

One involves his truthfulness under oath. As I have written before, anyone active in D.C. journalism in the 1990s (as I was, for the Atlantic and as editor of U.S. News) is familiar with Kavanaugh’s name. Back then, while in his early 30s, Kavanaugh was an active partisan member of Kenneth Starr’s investigative staff, working on president Bill Clinton. David Brock, at the time a fierce right-winger (and critic of Anita Hill), has written about how Kavanaugh was a fellow warrior in these political crusades. Washington journalists knew Kavanaugh as one of the more press-available members of Starr’s staff. Then, in the George W. Bush administration, Kavanaugh was White House staff secretary and, like anyone in this job, involved in both politics and policy.

During his confirmation hearings for the D.C. Circuit Court 12 years ago, Kavanaugh denied under oath that he had participated in certain specified partisan fights. Two senior, hyper-cautious Democratic senators—Patrick Leahy, and Dianne Feinstein—have, along with others, now come out with statements saying that they believe Kavanaugh was lying under oath in 2006, and is doing so again now.

Was he? This matters.

Every modern-era judicial nominee has mastered the art of dissembling, and pretending to have a completely open mind and a “I just call the balls and strikes” objectivity about every controversial issue.

But actual lying is something different. Clarence Thomas’s interlocutors believed that he was lying about Anita Hill, and the intervening years make it more likely they were right. This is the first time I’m aware of, since the Thomas hearings, in which senators opposing the nomination have come out and said: This nominee is lying under oath. It is worth knowing the truth before the now-or-never vote is cast.

The second question involves finances. There’s been only one genuine impeachment of a Supreme Court justice, back in 1804. But the threat of impeachment convinced another justice, Abe Fortas, to resign, in the Lyndon Johnson era.

The cause of Fortas’s problems was what now seem like penny-ante financial complications. A $15,000 fee for some seminars, news of a $20,000 annual retainer from a Wall Street figure.

Sure, that was 50 years ago, so you have to allow for inflation. But by comparison, Brett Kavanaugh has some major financial gray-areas in his recent past. The very large credit-card debts, suddenly paid off? As David Graham put it in the Atlantic:

The fact remains that Kavanaugh suddenly cleared at least $60,000 and as much as $200,000 in mysterious debt over one year—sums large enough that senators might well want to know who the sources of the payments were.

Maybe this all is nothing. But the Senate is ramming through a vote before anyone knows what’s there. And—the crucial point—if information comes out about his finances, or his truthfulness, or anything even one day after he is sworn in, it will be too late. As with Clarence Thomas, he’ll be there, to stay.

And as for the number of Republican senators who are saying: Wait a minute, let’s take our time, it matters to know the truth before giving someone a job for life? What is the rush?

Here’s the list of their names:

52 days to go.

Update: This morning, September 16, the Washington Post published an editorial (i.e., editorial-board statement, not an individual op-ed) with the title “The Senate Should Delay Voting on Brett Kavanaugh.” It says:

Republican efforts to rush through Mr. Kavanaugh have prevented a fair weighing of his nomination. The circumstances demand that Mr. Kavanaugh’s confirmation be delayed.

Suppose Brett Kavanaugh ended up with exactly 51 bloc-GOP votes on his side. Have you perhaps wondered how many votes the eight current justices received? Wonder no more. The tally also heightens the similarity in the Thomas and Kavanaugh cases:

Clarence Thomas, 52 votes

Ruth Bader Ginsburg, 96 votes

Stephen Breyer, 87 votes

John Roberts 78 votes

Samuel Alito, 58 votes

Sonia Sotomayor, 68 votes

Elena Kagan, 61 votes

Neil Gorsuch, 54 votes